Entry One, a Cinematic Monster: Jean Jacket

Jean Jacket in her true form during the climactic scene in ‘Nope’ (2022), directed by Jordan Peele

Christened Jean Jacket (henceforth JJ) by OJ, the main protagonist in the western horror sci-fi movie, JJ predominantly assumes the appearance of a UFO who pursues and consumes horses and humans in the arid ranch areas surrounding Los Angeles. After attempts to publicise and spectacularise JJ’s existence, the creature begins to hunt and devour those who sought to ultimately exploit and capitalise off her. This however does not deter the protagonists from risking their lives to tame her to capture their ‘Oprah shot’; video footage that would bring them great publicity and fortune.

Unlike typical portrayals of flying saucers as having an extra-terrestrial origin or being piloted by aliens, JJ defies such categorisation and is posited to be an apex predator: “It’s alive, it’s territorial, and it wants to eat us.” The equivocal nature of JJ can be interpreted as emphasising her monstrous essence transcending the binary distinction between normality and Otherness. Similarly, to the Xenomorphs in Alien (1979), this allows her to simply function as a reflection of societal fears of the unknown and unexplainable, especially considering her purpose and origins are shrouded in mystery. What is known about JJ is that she hovers over her victims and sucks them up into her ‘mouth’ when she assumes her saucer-like shape. According to Oleszkiewicz (2022), this is a homage and “explanation to the legends of alien abductions by tractor beam”. However, this function can be further attributed when JJ shifts from her conventional UFO appearance to an ethereal winged creature, matching that of Biblical depictions of angels.

Her celestial form conveys disturbing implications when considering the correlation between the UFO’s feeding process and the notion of human ascension to the afterlife. Moreover, it suggests that JJ is not the sole member of her kind and has been present and existed since the time preceding the Common Era, hinting at the possibility that the descriptions of Biblical angels draw influence from this creature or species. This further imbues JJ with an aura of alterity and unpredictability. The horror in which she instils can also correlate with her digestive process considering, her prey become ensnared within her digestive tract and endure a crushing demise after being ingested. Arguably it can be considered a liminal space between life and death that induces claustrophobia by visually presenting as constricted and bloody space. A skinned horse can also be visibly seen within her digestive tract by her victims and viewers, serving as a gruesome omen of the fate that awaits them and instilling horror in spectators. This can be explained through Kristeva’s (1982) essay on abjection, in which she refers the abject to the human reaction of horror to “a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other” (as cited in Felluga, 2015, p.3).

Additionally, the protagonist’s unwavering pursuit to obtain video footage of JJ offers an alternative societal function and reading, which, as Lee (2022) contends, could be used to explore the dangers of pursuing spectacle. The argument put forth by Cohen in this context is relevant, as he posits that “the monster stands as a warning against exploration of its uncertain demesnes” (1996, p.7). In the film, several characters attempt to engage with JJ despite the obvious danger that she proposes. Despite already having captured a shot of the supposed UFO, OJ risks his life to obtain the ‘Oprah shot’. The bloodshed that ensues after attempts to commodify JJ can be viewed in alignment with Cohen’s suggestion that interaction with monsters “declare that curiosity is more often punished than rewarded, that one is better off safely contained within one’s own domestic sphere” (1996, p.7).

Selected Bibliography

Cohen, Jeffrey (1996). Monster theory. Minneapolis Minn.: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Felluga, Dino Franco (2015). Critical Theory: The Key Concepts. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

Kristeva, Julia (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lee, Kole Lyndon (2022). The Meaning Behind Jordan Peele’s “Nope”: The Dangers of Pursuing Spectacle. Screencraft: https://screencraft.org/blog/the-meaning-behind-jordan-peeles-nope-the-dangers-of-pursuing-spectacle/

Oleszkiewicz, Anthony (2022, March 22). Nope: What’s the Story Behind That Alien Jean Jacket? Collider: https://collider.com/nope-alien-jean-jacket-explained/

Peele, Jordan (2022). Nope. United States: Universal Pictures.

Scott, Ridley (1979). Alien. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Entry Two, a Gender Monster: Scylla

A contemporary depiction of Scylla, illustrated by Sheppi-Arthouse on DeviantArt (2017)

First attested in Homer’s Odyssey, Scylla is originally depicted as a voracious monster having six heads and twelve dangling appendages, who resides in a cave on one side of narrow straits. Her modus operandi in every tale is consistent with that in Odyssey, where she seizes a mariner in each of her mouths as they pass by, and then devours them. Ovid’s Metamorphoses would later offer an origin story in which scorned and covetous Circe was the perpetrator behind Scylla’s monsterization. Synchronously, these aspects are predominantly adhered in subsequent adaptations and retellings, as exhibited in Miller’s Circe (2018). Her physicality however occasionally varies throughout mythography: rendered as possessing a woman’s head and torso, adorned with a sea creature’s tail, with ferocious dogs emerging from her midriff.

Despite her varied origins and physicality, they all suggest a comparable, if not identical, purpose. Hopman (2012, p.65) posits that Scylla’s voracity epitomises “a fundamental anxiety associated with the sea and its inhabitants in archaic thought.” This assertion is exemplified in the Homeric tale of hero versus monster, where Scylla represents a menacing embodiment of the sea. Odysseus, revered for his resourcefulness and wit, proves to be impotent against Scylla and results in the uncommon outcome of the monster emerging victorious. This is possibly attributed by her lack of erotic charm that does not liken her with other Homeric monstrous women, who are depicted as alluring yet perilous, while Scylla “just seems hungry” (Miller, 2013, p.317). Felton (2013, p.105) argues that such monsters “spoke to men’s fear of women’s destructive potential. The myths then, to a certain extent, fulfil a male fantasy of conquering and controlling the female.” While Odysseus had subdued and conquered other monsters, usually through intercourse, Scylla remains unvanquished and defies such a narrative.

Her monstrous metamorphosis offers a distinct interpretation, whereby Scylla reflects the prevalent anxiety and gynophobia within Grecian culture. Cohen’s proposition (1996, p.7) remains pertinent, as it posits that societal expectations concerning gender roles elicit apprehension, thereby engendering fear towards those who challenge conventional gender roles. Scylla typifies this assertion, as she is rendered monstrous due to her transgression of nymph-like expectations. Such alterity is inscribed onto and constituted through her impregnable physicality, and her abject shifting body, depicted by Miller (2018, p.49-50), arguably acts as a site onto which all these apprehensions are projected.

Miller’s depiction of Scylla may be interpreted as akin to Carter’s portrayal of Sophie Fevvers in Nights at the Circus (1984), both expressing the manifestation of the liberated woman who transcends conventional gender roles and embraces the process of becoming monstrous.

“Even the most beautiful nymph is largely useless, and an ugly one would be nothing, less than nothing […] But a monster […] she always has a place. She may have all the glory her teeth can snatch. She will not be loved for it, but she will not be constrained either” (2018, p.62).

Even her subsequent representations, where she undergoes sexualised recoding, is indicative of a degree of unconscious gynophobia within Grecian society (Hopman, 2012, p.180). Zimmerman corroborates this by underscoring the contrasting portrayal of her beautiful countenance and monstrous genitalia as a metaphorical representation of the revulsion that patriarchal societies associate with women’s bodies when they “behave in unruly ways” (2021, p.53).

Selected Bibliography

Carter, Angela (1984). Nights at the circus. London: Chatto & Windus.

Cohen, Jeffrey (1996). Monster theory. Minneapolis Minn.: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Felton, Debbie (2013). ‘Rejecting and Embracing the Monstrous in Ancient Greece and Rome’. In A. S. Mittman & P. J. Dendle (Eds.), The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hopman, Marianne Govers (2012). Scylla: Myth, Metaphor, Paradox. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, Madeline (2018). Circe. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Zimmerman, Jess (2021). Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology. United States: Beacon Press.

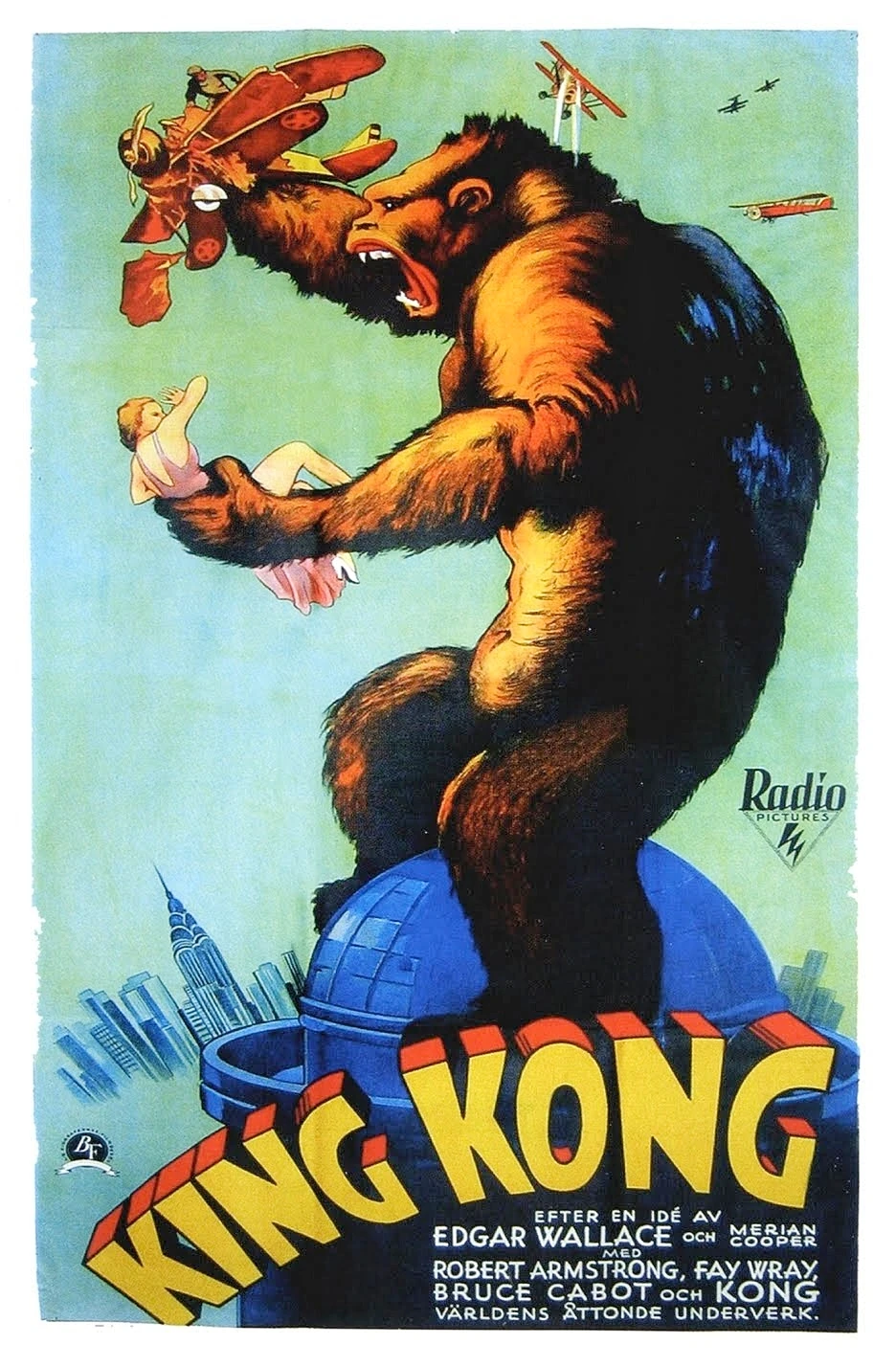

Entry Three, a Postcolonial Monster: King Kong

King Kong in scene from ‘King Kong’ (1933), directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack.

King Kong, a gigantic gorilla belonging to the Megaprimatus Kong species, debuted in the 1933 film of the same name. He was captured from his native home on Skull Island and transported to New York City to be exhibited as the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’. Since his inception, Kong has since featured in several sequels and spinoffs and has become an iconic figure in the history of cinema’s giant monsters. Despite his glorification in modern films, the subtext of his early incarnations implies that Kong functions as a xenophobic reading, a postcolonial critique, or an allegory for anti-colonisation.

Jeffrey Cohen contends that a monster is “an embodiment of a certain cultural moment—of a time, a feeling, and a place” (1996, p.4). Arguably, this thesis can be applied to Kong, wherein as a monster, he is evocative of the US’s societal apprehension and fear towards the black race following the economic crisis and colonial context in which the movie was made. Although never explicitly stated, there exists a prevalent theory that Kong, stereotypically, embodies the black race which can be evidenced in his physicality and actions. Cárcel (2021) elucidates that during times of economic depression and widespread unemployment, white workers exhibited fear and perceived black citizens as a threat, denigrating them based on race. Additionally, Americans ascribed superhuman abilities such as strength and sexual prowess to people of colour while simultaneously dehumanising them by likening them to apes.

Fanon (1952), argues that colonist and racist discourse invariably resorts to the bestiary, turning the colonised into beings of uncontrollable sexual desire (as cited in Cárcel, 2021). Kong stands as a symbol of the black race, metaphorized into a wild beast upon which all social discomforts are projected. Kong’s capture of Ann Darrow, a white woman, reflects the power dynamic between colonisers and colonised people. Much like the monster depicted in Marsh’s The Beetle (1897), this interpretation allows Kong to manifest the Eurocentric fear of the colonised Other and the possibility of role reversal.

Alternatively, the movie can serve as a parallel to colonialism and imperialism. Kong was taken from his natural habitat, metaphorically captured and chained, and brought to New York for the amusement and profit of white people (Dheeraj, 2017). This could be interpreted as a metaphor for colonisers extracting resources from colonised lands and bringing them back to the West for profit. Kong’s rebellion against his captors can be viewed as a movement by the natives to overthrow the colonial power, with his death signifying the crushing of that rebellion by brute force. It is possible that Kong’s destructive behaviour denoted possible chaos ensuing if the black race were given total freedom, or, alternatively, a warning and criticism against mankind’s desire to exploit colonised countries or nature for personal gain.

Regardless of the possible purpose of Kong’s functionality, it is possible to discern in his initial representation an ideological resemblance to the colonial systems of his era. This is considering his representation replicates the structure of racist depictions of people of colour that were prevalent at the time.

Selected Bibliography

Cohen, Jeffrey (1996). Monster theory. Minneapolis Minn.: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Cárcel, Juan A. Roche (2021). King Kong, the Black Gorilla. Quarterly Review of Film and Video.

Dheeraj, Jangra (10 March 2017). The symbolism of King Kong. Times of India: https://toistudent.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/news/top-news/the-symbolism-of-king-kong/19282.html

Fanón, Franz (2009). Piel Negra, Mascaras Blancas. Madrid: Akal.

Marsh, Richard (1897). The Beetle. Skeffington & Son.

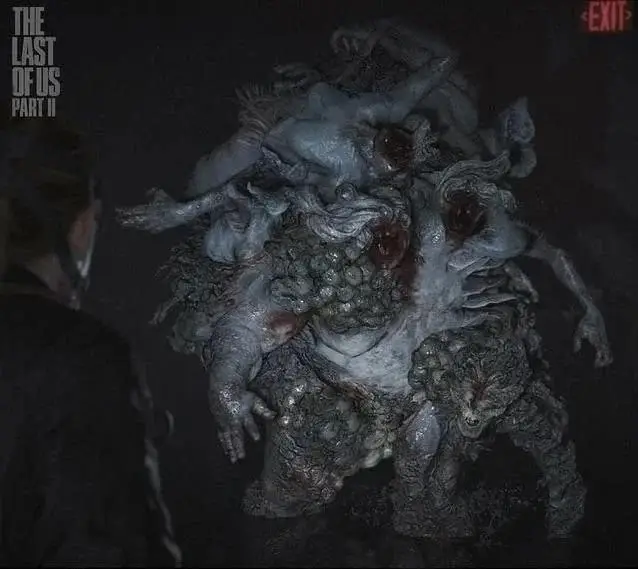

Entry Four, a Postapocalyptic Monster: The Rat King

The Rat King, a fifth class of Infected from ‘The Last of Us: Part II’ (2020), developed by Naughty Dog.

First introduced in the video game series The Last of Us (2013) and subsequently featured in the TV show adaptation (2023), the Infected are humans who contracted the Cordyceps brain infection (CBI), a parasitic fungal infection inspired by Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which devastated humanity within the franchise. After attacking the brain, the fungus hijacks the host’s motor functions and continued exposure to CBI results in horrific mutations that can be categorised into five currently known stages. The degree of exposure directly corresponds to the level of threat posed by the Infected, who gradually become less human in appearance as the fungus skews their features by growing out their orifices.

In addition to airborne spore transmission, the infection is primarily spread through bites from living hosts, leading to parallels with the zombies featured in Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) and sharing the reinterpretation of zombies being grounded on scientific plausibility. This reinterpretation is reinforced within the TV show, as its origins are elaborated and posits that the fungus, having exclusively targeted insects, underwent an evolutionary process due to global warming, which allowed it to subsist within and infect humans. Fischer-Hornung and Mueller argue that zombies, similarly to vampires, express “anxieties about invasions and the transgression of personal or national borders” (2016, p.12). This is applicable to the Infected considering their monstrosity can be attributed by their ability to spread their Otherness to their victims. Which additionally reflects apprehension regarding the collapse of civilisation. The resultant change in narrative introduces an additional function for the Infected, namely, to serve as a warning and a signal of the probable hazards that may arise because of global warming. Furthermore, the realistic grounding of human beings undergoing monsterization can arguably render the Infected more disconcerting compared to conventional reanimated corpses. This is tied to the interpretation of zombies manifesting the fear of being dehumanised, which is amplified within TLoU franchise due to the colonising nature of the CBI.

During an interview published by Rev3Games (2013), Druckmann, Co-President of Naughty Dog, confirmed that within the initial 48 hours of contracting the fungus, the Infected engage in a futile struggle against the infection. He also draws a parallel between the infection and the common cold, whereby the host’s response to the infection is akin to sneezing; they lack control, and despite their efforts to resist, succumb to the infection. This is evidenced in the video games where Infected, during the early stages of infection, can be heard crying and gagging while consuming humans. This can arguably encapsulate and resonate with Larkin’s preposition of the humans fearing turning into enslaved zombies (2006, p.26). The loss of agency and autonomy, fundamental aspects of being a human, reduces the Infected to mere vessels for the fungus and places them within a permanent state of liminality between human and Other, and between life and death. Cohen’s thesis is applicable in this instance considering an Infected incoherent body can be perceived as resisting being placed within any systematic structuration (1996, p.6).

The classification of the Infected as Other or deceased is discerned through their state of decay, grotesque mutation, and loss of motor control. However, the question of their retained consciousness raises doubts about their status as human and living beings. Kristeva’s theory on abjection can be aptly applied to the Infected as abjection arises not from lack of cleanliness or health, but from anything that disrupts identity, system, and order, that does not adhere to borders, positions, or rules, and exists in a state of ambiguity, in-betweenness, and composite (1982, p.4). The Infected can be interpreted as an amalgam of life and death and arguably align with Kristeva’s assertion of the corpse being the utmost abjection as it is death infecting life (p.4). Thus, arguably allowing them to embody Foucault’s argument of a monster being “a mixture of life and death […] the transgression of natural limits, the transgression of classifications” (2003, p.63).

Selected Bibliography

Boyle, Danny (2002). 28 Days Later. United Kingdom: DNA Films. UK Film Council.

Cohen, Jeffrey (1996). Monster theory. Minneapolis Minn.: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Davidson, Arnold Ira., & Foucault, Michel (2003). Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France 1974-1975. United Kingdom: Verso.

Druckmann, N., Mazin, C., & Johnson, K (2023). The Last of Us. HBO.

Fischer-Hornung, Dorothea. & Mueller, Monika (2016). Vampires and Zombies: Transcultural Migrations and Transnational Interpretations. University Press of Mississippi.

Kristeva, Julia (1982). Powers of horror: An essay on abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

Larkin, William S (2006). Res Corporealis: Persons, Bodies, and Zombies. In Zombies, Vampires, and Philosophy: New Life for the Undead. Chicago: Open Court.

Naughty Dog (2013). The Last of Us. Sony Computer Entertainment.

Rev3Games (2013). The Last of Us NEW GAMEPLAY! Infected Details, Story, Crafting, and MORE! Adam Sessler Interview. YouTube.